“Corporate medicine has become one of those phrases that have no real definition but still make most physicians shudder” (Cook, 1999). Nearly a decade after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated individuals to receive healthcare and subsidized insurance, the structure of the U.S. healthcare system remains unchanged and problematic.

As I have matured, I have come to appreciate the fact that if something is too difficult to achieve a good fit, maybe it is not meant to be, and there is a better way.

Let us consider some examples of a good fit and a problem solved from our healthcare history. In the 1920s, even wealthy Americans were unable to pay hospital fees, and many were facing bankruptcy. Doctors were not receiving payment for their fee-for-services from patients, and Dr. Justin F. Kimball of Baylor University wanted to ensure hospitals were paid. He invented the method of prepayment during a time when hospitals were mostly nonprofit community institutions. Dr. Kimball solved the university hospital’s unpaid bill problems by discovering the delinquencies were coming from local schoolteachers who were unable to pay. Kimball resolved the issue by offering teachers covered hospital stays of up to three weeks for 50 cents per month. 1,250 Dallas teachers enrolled in the first health plan of what would come to be known as Blue Cross. In this example, the employer (the school district) directly contracted with the provider (the hospital) to provide access to care.

Another example of a problem solved is when Henry Kaiser collaborated directly with Sidney Garfield, MD who had previously saved his own hospital from bankruptcy at the height of the Great Depression by shifting away from fee-for-service to collecting a prepayment of a dime-per-day from aqueduct workers in exchange for his comprehensive services. This shift away from fee-for-service to prepayment and group practice gave rise to what would be known as health maintenance and wellness, emphasizing prevention and early detection or the “new economy of medicine.”

Another case of our American, employer-financed healthcare system is with the coal miners. After a life-risking career in mining, miners often developed occupational illnesses and diseases. In 1946, President Truman, Julius Krug, and UMWA President Lewis made a deal that miners would have extended health care post-retirement, funded by their last employer known as The Promise of 1946 (Krug-Lewis Agreement). For decades, contracts required this stipulation. Retirement health care was so critical to union miners that they were willing to strike and accept lower salaries from coal operators to maintain it.

Thus, we can see some examples of the American ingenuity of employers solving their problems and achieving a “good fit” directly and on a local level. It has been said in healthcare that, “if you do what is right for the patient, everything else will fall into place.” After all, we as physicians went to school and got our training, so we could serve our patients. We as physicians all know that the real value in what we do is doctor to patient, or in our employer-financed healthcare system, clinic to company.

As billions of dollars are spent on lobbying and healthcare rises on the political agenda, I fear that it takes us further away from restoring what has been lost in healthcare.

I operate a clinic in San Antonio called Direct Med Clinic. In that capacity, I feel privileged to satisfy the needs of the community in ways I have described above. The Direct Primary Care (DPC) model provides access to healthcare to those who might otherwise go without it because premiums or deductibles are too high. This is done by contracting directly with small employers who value their employees but who cannot afford insurance. This allows a physician to also see to the needs of large employers through onsite clinic services. For medium-sized employers, affordable access is provided through a “near-site” model.

Practicing this way allows the use of technology to care for our patients freely by whatever modality is a good fit. It has been said that “technology has far outgrown reimbursement systems”. Technology is a tool just as any surgical instrument. In the hands of an experienced physician, it can be used that way. Patients can use HIPAA compliant secure app-to-text, upload photos, videos or do video chat.

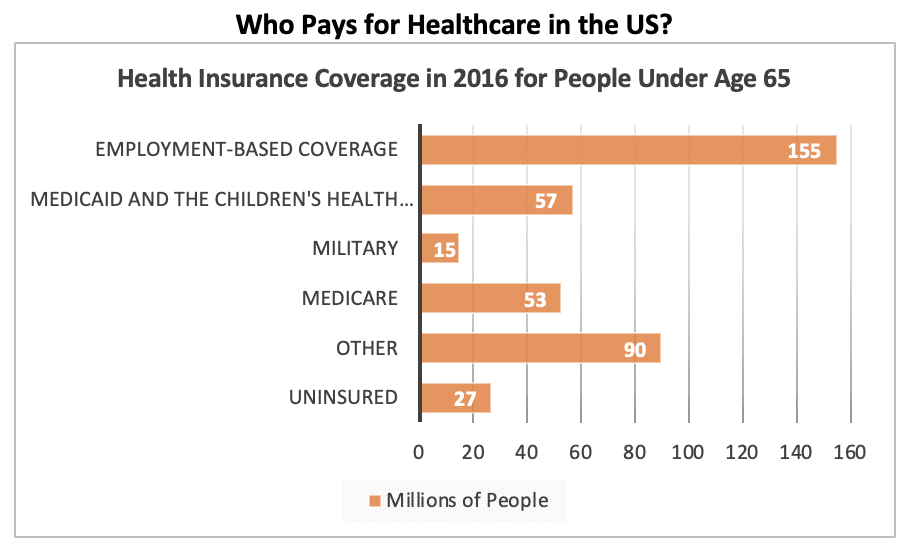

Despite government subsidy of healthcare, it is still the employer that pays for the majority of healthcare in this country.

According to Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans 2018, the average per-employee cost tops $13,000 among employers with 500 or more employees. With all this cost, it is ironic that employers do not actually pay those who actually provide the care.

To the extent we can restore the direct relationship, I believe we align the incentives to what was the foundation of what our American free market and employer-based healthcare system was based on. The development and growth of the Free Market Medical Association is an example of this principle. Through price transparency, providers and healthcare facilities demystify the cost of healthcare and create a free market where the purchasers of healthcare can shop for what they need and obtain it directly and on a local level.

As we look for solutions to our healthcare problems, let us be wise and not try too hard to make something fit if there is a better way.

References

Cook, B. (1999, October 01). Redefining Corporate Medicine. Retrieved August 7, 2019, from https://www.aafp.org/fpm/1999/1000/p9.html

Field, M. J., & Shapiro, H. T. (1993). Origins and Evolution of Employment-Based Health Benefits. In Employment and health benefits: A connection at risk. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

How it all started. Retrieved August 07, 2019, from https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/our-story/our-history/how-it-all-started

Crosson, J. (2006). Dr. Garfield’s Enduring Legacy–Challenges and opportunities. The Permanente Journal, 10(2). doi:10.7812/tpp/05-146

Coal Act. Retrieved August 7, 2019, from http://umwa.org/for-members/pensions-retiree-info/coal-act/

Schmidt, G. United mine workers of America welfare and retirement funds. Retrieved August 07, 2019, from http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol16/iss2/4

Joint Committee on Taxation. Retrieved August 10, 2019, from https://www.jct.gov/

Mercer National Survey. Retrieved August 9, 2019, from https://www.mercer.us/what-we-do/health-and-benefits/strategy-and-transformation/mercer-national-survey-benefit-trends.html

About FMMA. Retrieved August 9, 2019, from https://fmma.org/about-us/

Roger Moczygemba, MD, graduated from Texas A&M University Health Science Center – College Station in 1992. Is specialized in General Family Medicine and Occupational Medicine, and is the owner of Direct Med Clinic in San Antonio, Texas.

Article originally appears in Bexar County Medical Society’s San Antonio Medicine Magazine.

Recent Comments